Empowering weather and climate forecast

Interview: Cindy Perscheid

Interview: Cindy PerscheidCindy Perscheid holds a BA and MA in computer science from the Hasso-Plattner-Institute and recently finished her PhD in Bioinformatics there. She now works as a software developer at Ambrosys GmbH. |

|

Q: Worldwide, women only make 77 cents for every dollar earned by men. Two thirds of Mexican women over 15 have experienced violence. Iran is outraged over a woman who was killed for wearing her hijab incorrectly. Do we not have more important fish to fry in the gender equality arena than getting women into computer science and physics? |

| Cindy Perscheid: I do not think this is a fair argument, as we could formulate it similarly for the actual climate crisis and the ongoing war in Ukraine. I agree, though, that one issue might be more pressing than the other, but that does not automatically render them irrelevant. This way of argumentation further ignores mutual dependencies, as progress in one area can foster the same in another: if we promote more women in STEM fields, we will foster gender equality and by that also (long-term) improvements in other areas like gender pay gap. If we create role models and allow women to step into the same place as men, we start to consider them to be truly equal and no longer be an less valuable abnormality in our patriarchal society (which I believe is one of the inherent causes also for violence and gender pay gap happening). |

|

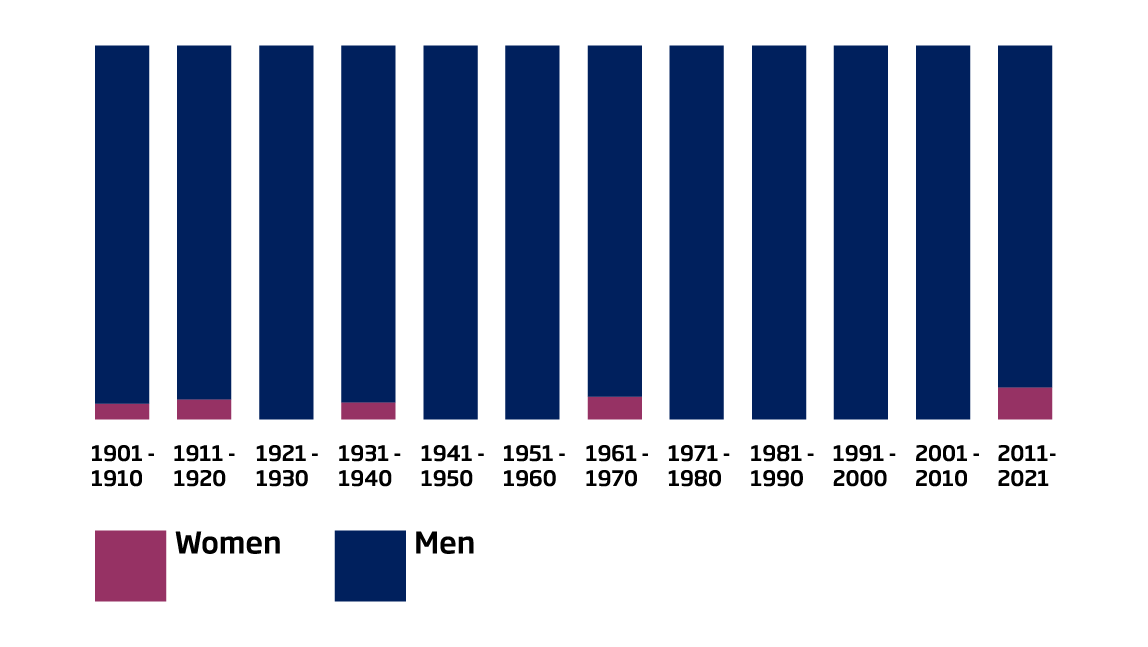

Q: In many areas, gender equality has progressed over the decades. Female CEOs, prime ministers, elite soldiers, or truck drivers are a common sight. Can you explain to our readers why physics and even more computer science are trailing the overall trend so stubbornly? |

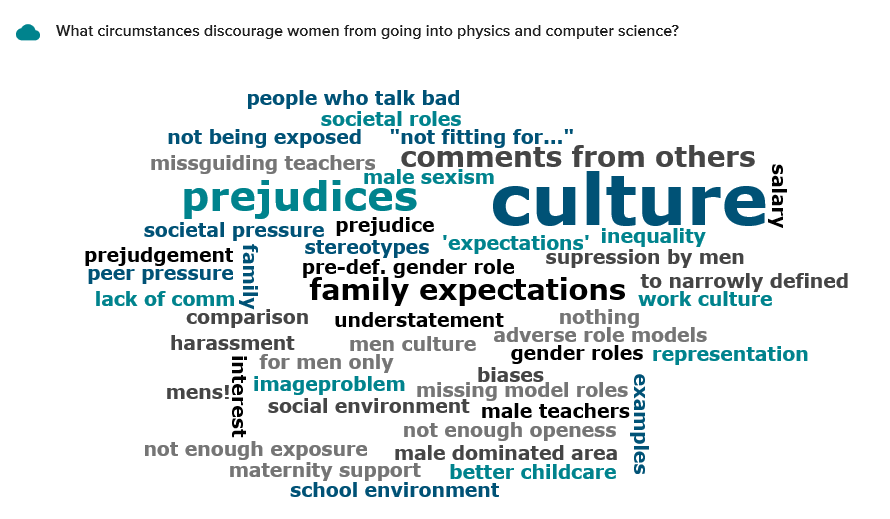

| Cindy Perscheid: Though we have progress in many areas, I do argue that we are still far away from where we have be if we want to call it true gender equality. Why there are so few women in STEM - and physics and computer science, in particular - for sure cannot be answered with one simple sentence. From my very personal experience as a mother, though, I can say that children are confronted from a very early age on with gender stereotypes: colors, clothes, and toys that are for boys or girls only, or one gender being generally better at/more interested in a particular topic than the other. These gender stereotypes negatively influence the development of a kid's personal preferences, as they limit possibilities to only a restricted range. There is actually a nice graph with numbers from the U.S. that backs up these very subjective assessment: While there was a high percentage of female computer engineers up until the middle 1980s, numbers decreased fast afterwards. Coincidentally, that happened around the time the personal computer started to move in to family homes - and was marketed mainly to men and boys. This thought has manifested since then into our minds. Gender marketing has even increased in the last years, so it is no surprise that things do not really get better/progress so slowly. |

|

Q: Scientific work is usually judged in a more rigorous, systematic way than, let’s say, managerial work. Shouldn’t this mean that the world of science is overall more permeable to skilled women than other work areas? |

| Cindy Perscheid: Most of the people do not quit because they are not talented enough or do not like what they do, but because the framework conditions make it impossible to work any longer in that area. The world of science has many structural problems that make it harder to cope with for women. Due to our patriarchal society, it is more likely that women stay at home when starting a family, they take over most of the care work and thus often only start in part-time jobs when returning to the work force. For research, this is a killer: you are expected to work on strict budget plans and constantly generate scientific output. I experienced that at work, too: A colleague of mine had two parental leaves (1 year each) during her PhD. While her research topic was innovative when she started her PhD, at the time she now comes to finish it, it is nearly outdated. |

|

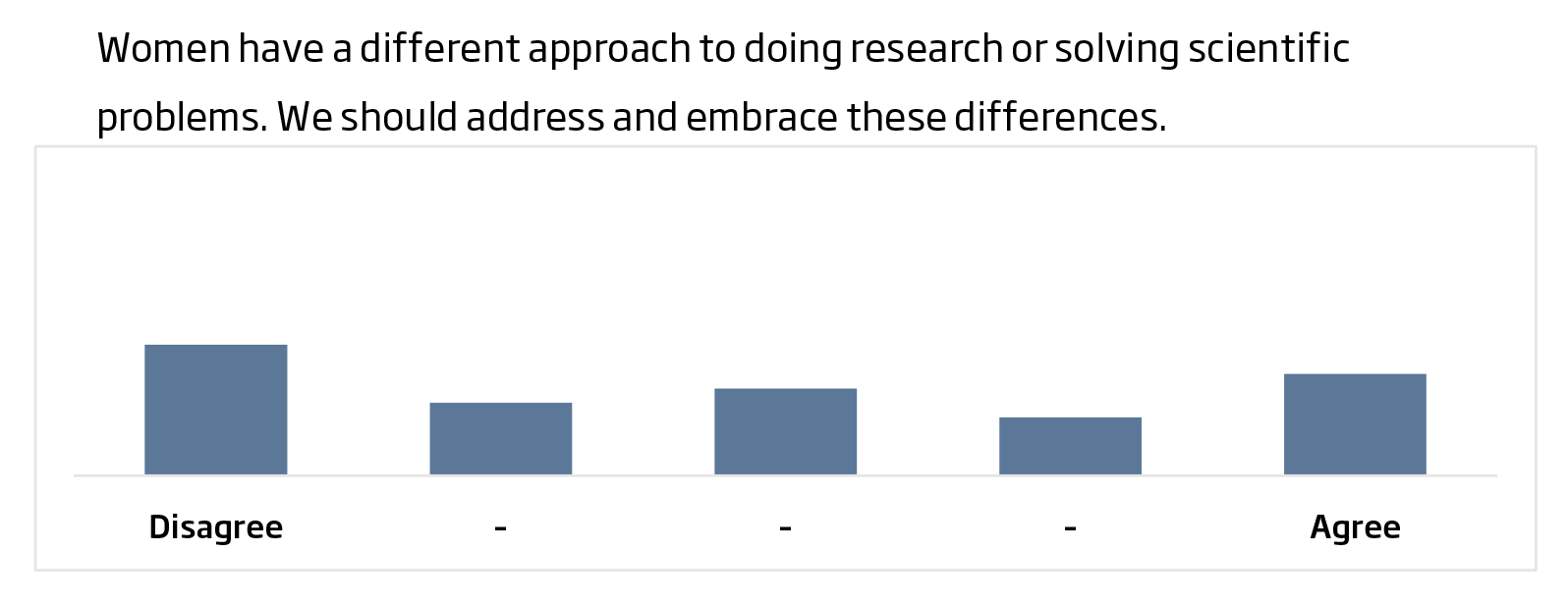

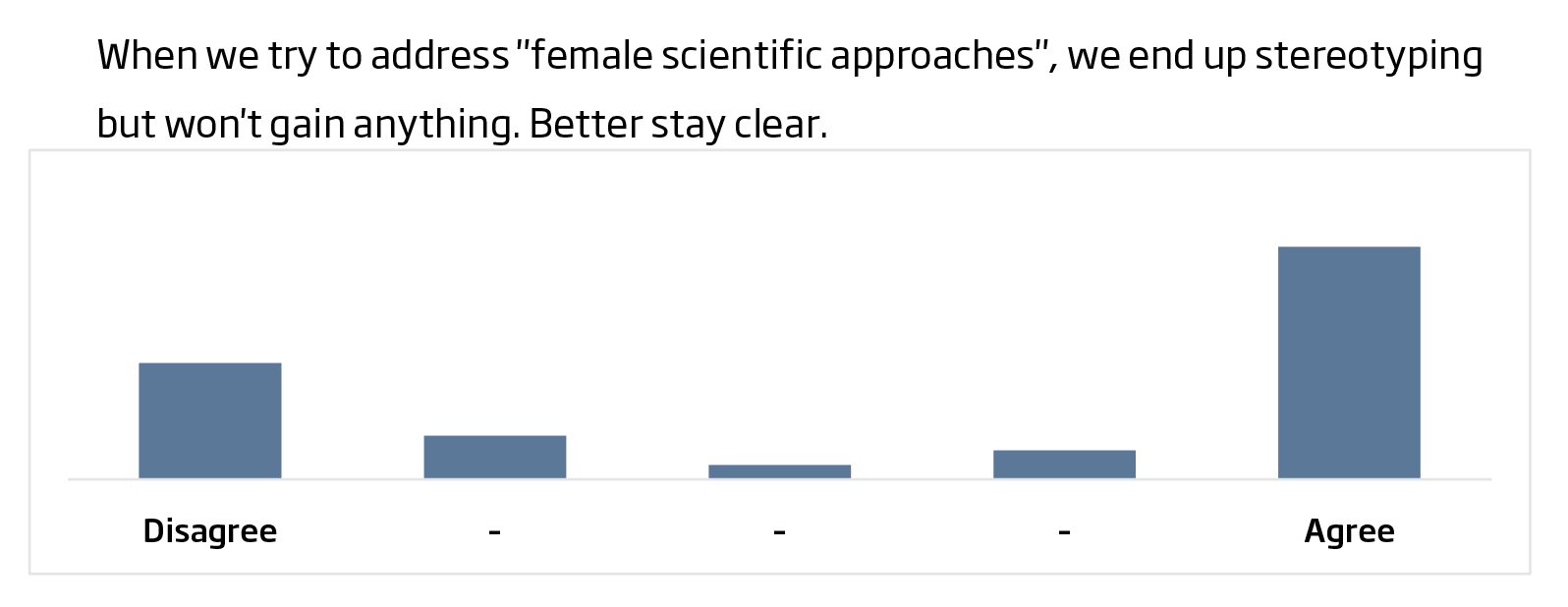

Q: In a recent poll we conducted with a group of scientists, the majority agreed that a combination of male and female thinking leads to better scientific results. Yet most participants refrained from actually denoting or describing such female thinking. If we believe in differences between male and female brains, why can’t we discuss them? |

| Cindy Perscheid: I do question that belief. We should stop this binary separation of humankind into "male" and "female" - this again just manifests gender stereotypes and falls short of reflecting overall diversity. I instead encourage to think in a wider spectrum: there are *people* with strong communication skills, there are *people* with strong analytical skills, there are *people* that are highly empathic, there are *people* that think highly strategic. True gender equality can only come if we stop to think binary but instead acknowledge that we have a diverse spectrum of different people. |

|

Q: Many initiatives for gender equality we see in scientific organizations feel anemic. Like: OK, we do it, because it’s expected today. Would you deliver us a short but fiery plea as to why it is in the very best interest of each research institution or business to crank up the ratio of female research staff? |

| Cindy Perscheid: Simple as is: you are currently missing approx. 50% of the brilliant minds (assuming brilliant minds are distributed equally across men and women) just because of gender. If you want the brilliant females to join you, you need to encourage them by creating female role models. |

|

Q: Let’s say there will be a project MAELSTROM 2, with some budget reserved to support gender equality. What are your three most out-of-the-box ideas on how to spend? |

| Cindy Perscheid: If I could choose, I would take that money away from the project to start at the root of all that evil: lobby for gender neutral (toy) marketing and education (for both kids and parents) to break up gender stereotypes in the heads of people. All children should grow up with a truly free choice on pursuing their personal interests. Unfortunately, that is currently not the case. If I had to spend the money project-related: a) make room for paid parental leave - for ALL employees/researchers b) foster (true! not "we still expect the same work load but pay half the wage") part-time work for everyone and try out work models with shared responsibilities (also in the management) c) allow female employees/researchers to participate in networking events to build up ally networks, e.g. international conferences like the "Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing" or "European Women in Computing”, but also smaller local events (I do not know if something like this exists for the physics world, though). |